Beyond the Music: Prayer & Pokémon GO

Devotional and Digital Visions of Augmented Reality

September 6, 2025 | By: Hazzan Matt Austerklein

Photo by Lukas Meier on Unsplash

“Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

Religion is augmented reality. It tells us that our bodies, communities, environment, and universe are not simply scientific facts, but the dramatic stage upon which a greater cosmic drama unfolds. While our eyes may behold the world as it is, the spiritual person senses that there are powers beyond — gods, angels, demons, spirits, and other energies which influence us, for good or for ill.

That being said, some cosmic dramas have more characters than others. Animist cultures of all stripes, including in India, Africa, and Southeast Asia, ascribe independence and spiritual agency to plants, animals, and landscapes. Organized religions, whether ancient or Abrahamic, also developed great hosts of angels and demons amidst whose celestial conflict the knight of faith must stand his ground. Awash in spectacle, these religions inspire us through the mystery and mythology of infinite spiritual personalities, brimming with powers both seen and unseen.

But we don’t have to look to religion to understand this. All we have to look at is children’s television.

Kids TV offers families a popular animism in which all things have the potential for a personality. My children call this when “everything has a smile and eyes.” City Island, above, is a great example. When the world of inanimate objects, animals, or imaginary beings become personified, we feel surrounded by an infinite, caring community of sentience — especially if it has a catchy theme song. Such a cartoon view of the world reflects our heartfelt desire for our kids to grow up confident and unafraid. Even if real tigers are fierce predators, we’re more than happy for our kids to meet Daniel Tiger and give him a hug.

Yet the Hebrew Bible was — and is — a radical departure from this cartoon fantasy. Rather than imagining a multitudinous world of natural and supernatural characters, it reduced the cosmic drama to a principal cast of two: the human being and God.

As the Dutch Egyptologist Henri Frankfort wrote:

“To Hebrew thought nature appeared void of divinity, and it was worse than futile to seek a harmony with created life when only obedience to the will of the Creator could bring peace and salvation. God was not in the sun and stars, rain and wind; they were his creatures and served him (Deut. 4:19; Psalm 19). Every alleviation of the stern belief in God’s transcendence was corruption. In Hebrew religion—and in Hebrew religion alone—the ancient bond between man and nature was destroyed. Those who served Yahweh must forgo the richness, the fulfillment, and the consolation of a life which moves in tune with the great rhythms of the earth and sky.”1

This sounds like a major bummer for the cartoon lovers among us. At the same time, Israelite religion was also profoundly humanistic. By not engaging with the threat of demons or the thrill of natural deities, the Hebrews focused their passion upon humanity. With each person created in the image of God, questions of how to act justly and live kindly were among the sources of life’s most profound meaning. In the face of a divine covenant, everything non-human — even angels — effectively became minor characters.

But this is not the end of the story. As all monotheistic religions evolved, each rediscovered the richness, fulfillment, and consolation of the old pagan approach. Whenever mysticism returned, so did the old magic and its stories of a bustling, animated universe of spiritual significance, waiting for the adept apprentice to learn its secrets and harness its power.

And with that, we turn to Pokémon GO.

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

Pokémon GO is an augmented reality video game for the smartphone which allows players to catch, train, trade, and battle digital monsters from the Pokémon cartoon and trading card franchise. Formed by Niantic, a spinoff company from Google, the game employs geo-tracking software to create an entire virtual world of collectable Pokémon embedded within real life, accessible only through the magical prism of the Pokémon GO smartphone app. For those who enjoy digital collecting, Pokémon, and mastering vast systems of esoteric knowledge, it is a dynamic dopamine generator with almost six million active players worldwide.

And it lives in our house.

For no more than thirty minutes (baruch hashem) a couple of days a week, one of my children explores our very real world through the very unreal, digitally-enhanced lens of Pokémon GO. The religious dynamics of this app both fascinate and frustrate me to no end. In many ways, the worldview behind Pokémon is an extension of Japanese Shintoism and its concept of kami, in which natural and mythical phenomena take on spiritual significance.2 In other words, Pokémon is derived from Japanese folk religion’s own version of “smile-and-eyes.”

Like the traditional pagan view, the promise of Pokémon GO fills every corner the world with potential meaning beyond what the eye can see. Yet with this comes a troublesome tradeoff: the commodification of our physical world as a permanent arena for collecting digital Pokémon and their myriad accessories. Thus have I driven to far off places, taken the kids on Pokémon-GO family walks run by the park service, and even opened the app on business trips abroad — all for the love-born promise of acquiring invisible monsters from an alternate universe.3

That Pokémon GO reflects a religious sensibility is further emphasized by its use of the calendar. Whereas world religions have predictable festivals of varying lengths throughout the year, Pokémon GO has an endless, thrill-optimizing series of “fests” and “community days” in which certain Pokémon or other digital tokens are most felicitously collectable. Able to compute the psychological desires of millions of players, the Niantic app schedules these surprise holidays to give gamers a sense of community and the chance for constant advantages on their endless quest.

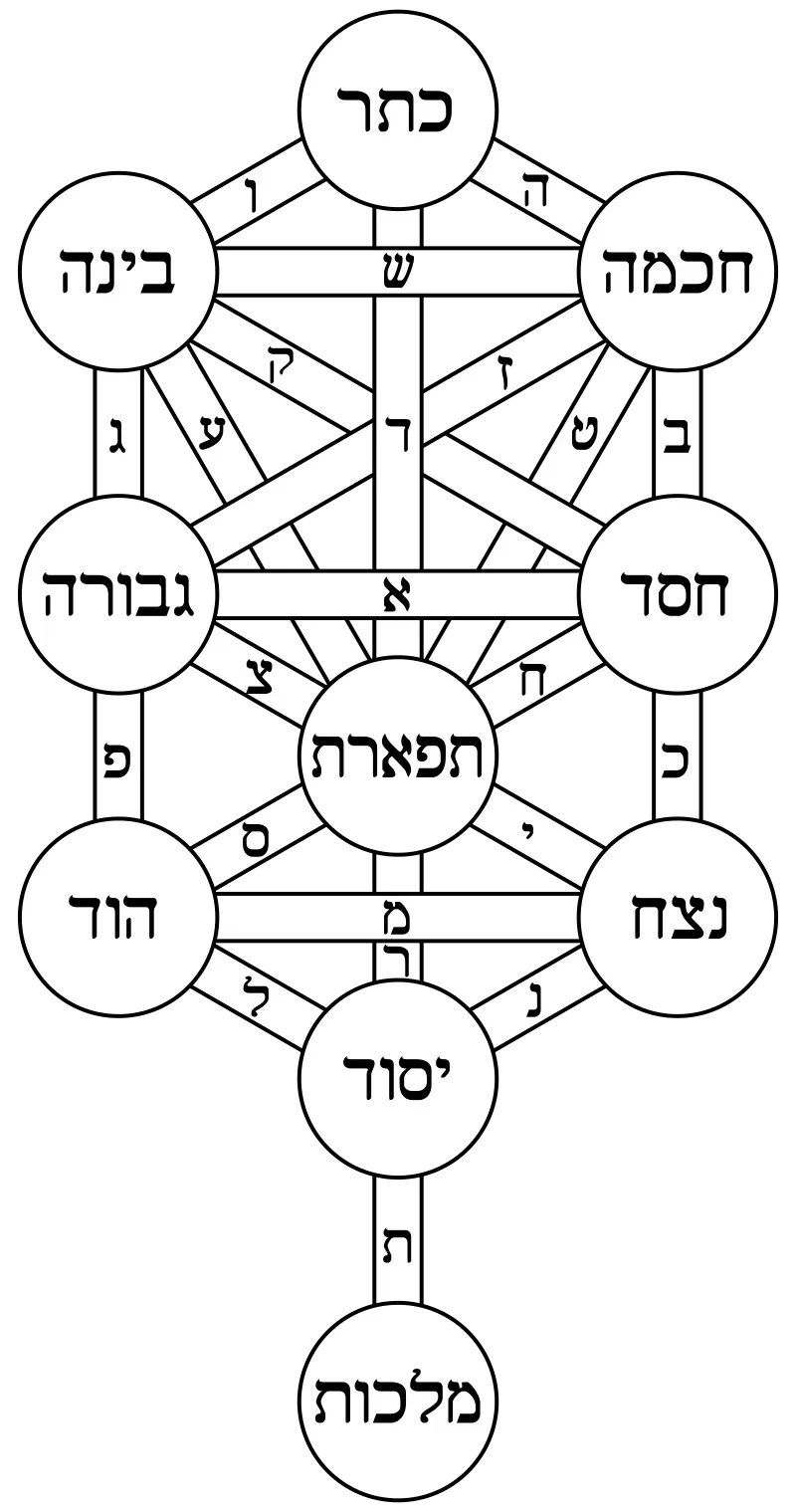

As I got to know our world through the prism of Pokémon GO, it struck me that its unseen reality was not unlike the dynamic world of Jewish mysticism. Kabbalah includes its own soaring strata of angels, demons, and kelippot — the evil forces which imprison the divine light within us. These demonic powers are thought to fill our very air, surrounding us at all times. And as Rabbi Isaiah Horowitz (1555-1630) wrote, both prayer and music serve as powerful weapons against them:

“Prayer too vanquishes many wars, that is the kelippot and the adversaries which fill all of the world’s air. And it will not escape their grasp unless they are cut down by the recitation of pesukei dezimra.”4

Accessing this augmented kabbalistic reality of depends on sensitizing oneself to religious life, giving one the ability to geo-track through the mystical levels of existence. During my PhD research, I discovered this in a fantastic story from Yehudah Leib Zelichower, a cantorial moralist and author from late seventeenth-century Europe. In his Sefer Shirei Yehudah (1697), he recounts a tale of the power of melody against the unseen foes of prayer:

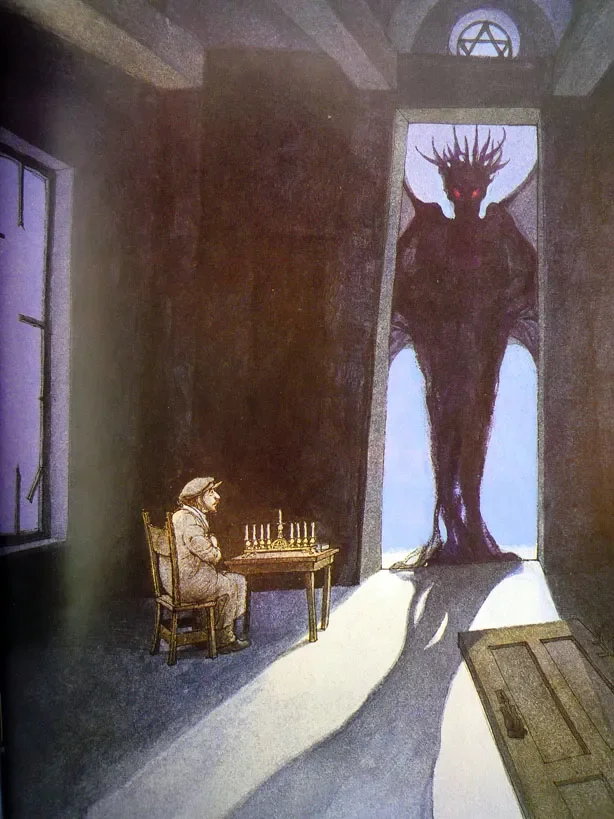

Another Jew faces a demon, from Herschel & the Hanukkah Goblins

“Truly, I heard it from a man of faith…who told me the tale of what happened to a pious man who led prayer on the High Holy Days…Amidst the tefilah, the pious man saw the kelippot of impurity, G-d help us, rising before him to wage war against him to hinder his prayer, so that it would not ascend on high to the Creator!

What did this pious man do? He ceased from his first melody, which belonged to that poem (piyyut), and began to sing in a bitter voice with a different, spiritually-arousing melody, and from this he was deeply moved and cried greatly. And on account of this, the kelippot of impurity were cut down, the accusers were silenced, and the waylayers and meddlers went on their way….And when the pious man saw that these destroyers, God protect us, had fled, been cut down, and removed so that his prayer was meritorious and pure, he returned to the prayer just as he began, with its appropriate melody.

At the same time, the permanent cantor was standing behind the pious man, and laughed at him for stopping his prayer and departing from the first melody which belonged to that prayer, reasoning that he had made a mistake. The pious man had sensed this, but he did not hasten his prayer due to [this cantor]’s folly. And after he finished his prayer he said to the cantor: “Why did you laugh at me? For I did this with clean hands and a pure heart! Know that this year, you shall surely die.” And [the cantor] inquired of the pious man why he had done this, and he recounted to him the whole story of what had happened during his prayer.”5

This dynamic story depicts a world in which music was part of the spiritual weaponry of the prayer leader. Tasked with the redemption of the Jewish people, the prayer leader embraces an almost shamanic role in the mystical battle against the kelippot, one which even pushes against the community’s body of received, traditional melodies in order to enact its magical ends. To wield such power, one must possess the piety-granted portal into the unseen spheres of kabbalistic struggle— i.e. the Pokémon GO of Prayer.

Whether in feeling the presence of HaShem, prevailing on the battlefield of prayer, or harvesting virtual fields of Pokémon, sensitivity to the unseen is at the heart of the religious experience. I can’t say that I don’t have problems with the neo-shintoism of Pokémon GO and its powerful distractibility from human life — problems that the ancient Israelites (and the LORD) also had with paganism.

Yet I think we have something to learn from the gamer’s powerful role in these unseen worlds. We too should approach life with a mission to see beyond. Not a pagan struggle to placate or battle with the powers-that-be, but a principled existence with transcendent validation. We should see the world as teeming with fantastic opportunities for mitzvot — a lifelong game which can be unlocked each day by spiritual sensitivity, not via a smartphone app. And while cartoons are fun and even comforting, we should ultimately help our children and each other connect with the ultimate “smile-and-eyes:” God. For it is this holy smile which looks back at us, and at times we see glimpses through the eyes of others, created in His image.

Footnotes:

1 Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society & Nature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978): 343.

2This should also be recognizable from the shinto-influenced book and TV series by Japanese author and organization expert, Marie Kondo.

3When Pokémon GO came out in 2016, there were upwards of 230 million players worldwide. This led to conflicts with mainstream society, like this one:

4"גם התפלה היא כובשת מלחמות רבות, דהיינו הקליפות והשטנים אשר הם מלאים בכל אויר העולם."ולא תוכל התפלה לעלות אם לא כשמחתכין את אלו בפסוקי דזמרא, cited in: Edwin Seroussi and Tova Beeri, “Rabbi Israel Najara in Ashkenaz,” Kabbalah 33 (2015): 66 [in Hebrew].

5Yehudah Leib Zelichower, Sefer Shirei Yehudah, 26a-b.

This article originates on Hazzan Matt Austerklein’s Substack, Beyond The Music.